In May 1972, several people broke into the Democratic National Committee’s (DNC) headquarters in Washington DC. The DNC housed its head office in the now infamous Watergate complex. During the break-in, the prowlers planted “bugs” and photographed documents. But, the wiretaps proved faulty. So, a month later, the burglars broke into the complex a second time. And, this time a security guard caught them in the act. The guard called the police and the burglars were arrested. Initially, the entire event seemed strange. Why, on earth, were these seemingly random burglars trying to monitor the DNC’s headquarters?[1]

In the days that followed, it appeared that the burglars might not be random individuals after all. Detectives, for instance, found the phone number of President Richard Nixon’s reelection committee among the prowlers’ belongings. So, did the White House have some sort of connection to this criminal action? In August 1972, President Nixon spoke to the nation in an attempt to alleviate the growing suspicions. He assured the public that the White House had no connection to the break-in.[2] Evidently, most voters believed their president, and Nixon went on to win a staggering victory that November. He gained more than sixty percent of the vote and won forty-nine of the fifty states. In the Electoral College, he crushed his Democratic opponent 520 to 17 votes. Poor George McGovern only won Massachusetts and the District of Columbia.[3]

But, the Nixon White House was most certainly connected to the Watergate affair. A few days after the break-in, for example, Nixon had arranged to provide “hush money” to the burglars. The White House also tried to enlist the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to help impede the Federal Bureau of Investigations’ (FBI) inquiry into the crime. Eventually, seven conspirators were indicted on charges relating to the Watergate break-in. At the urging of Nixon’s advisers, five pleaded guilty to avoid trial. The other two (former Nixon aides G. Gordon Liddy and James W. McCord Jr.) were convicted in January 1973. Nonetheless, questions about the extent of the attempted cover-up remained.[4]

By this time, an increasing number of people, including Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, and trial judge John J. Sirica, began to suspect that the Watergate break-in was just the tip of the iceberg and that senior White House officials had been partaking in significant illegal and illicit activities. In response to these concerns, Attorney General Elliot Richardson appointed Archibald Cox in May 1973 as special prosecutor to lead an investigation into the Watergate affair. Also, that month, a special Senate Watergate Committee began to hold public hearings on the scandal.[5] As we will see, the ensuing investigation by the media, Department of Justice, and Congress revealed that Nixon had been abusing presidential authority in profoundly disturbing ways.[6]

In July 1973, Alexander Butterfield, a former presidential appointments secretary, revealed in his congressional testimony that since 1971, Nixon had recorded all conversations and telephone calls in his office.[7] As my former PhD advisor, distinguished presidential historian Allan Lichtman puts it, this revelation “launched a bombshell.” If prosecutors had access to those tapes, they could determine with certainty the extent to which the president was involved with the Watergate affair. Yet, Nixon and his lawyers refused to hand over the tapes, arguing that to do so would infringe upon Nixon’s “executive privilege” to withhold confidential conversations between the president and his advisors.[8] When Archibald Cox refused to stop demanding the tapes, Nixon decided he should be fired. This order prompted several leading Justice Department officials to resign in protest on the evening of October 20, 1973 in what has been dubbed, the “Saturday Night Massacre.”[9]

Throughout 1974, more ties between the White House and the Watergate scandal surfaced. In March, a new special prosecutor appointed a grand jury that went on to issue indictments against even more of Nixon’s former aides on various charges relating to the scandal. The jury labeled Nixon an “unindicted co-conspirator,” since, constitutionally speaking, it has remained unclear whether a sitting president can be indicted. As well, on July 24th, the United States Supreme Court addressed the controversy regarding the Nixon tapes. In United States v. Nixon the Court declared that while the president has a presumptive right to withhold confidential conversations, that right can be set aside if there is a demonstrated, specific need for evidence in a pending criminal investigation. Hence, the Court ordered Nixon to hand over the tapes.[10]

Three days later, the House Judiciary Committee passed the first of three articles of impeachment. After the Committee passed the last article of impeachment on July 30th, top Republicans including Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott and House Minority Leader John Rhodes alerted Nixon that the full House would likely vote for impeachment. They also warned him that a subsequent trial by the Senate would probably result in a conviction. Reading the tealeaves, so to speak, the pragmatic and shrewd Nixon resigned from the presidency on August 8, 1974, becoming the first president to do so.[11]

Nixon resigned before the full House could vote on the articles of impeachment. Contrary to popular belief, then, Nixon was not impeached. Impeachment proceedings start in the House, usually with an investigation by the Judiciary Committee. If committee members decide there are grounds for impeachment, articles of impeachment are drafted. After a favorable majority vote, the Committee may recommend those articles to the full House. If the House ratifies the articles, the case proceeds to the Senate for a trial. After the trial, the Senate can move to convict and remove the president by a two-thirds majority vote.[12] Thus, the official impeachment proceedings against Nixon had only just begun when the president resigned. The grounds for impeachment were so strong that resignation seemed to be the only way to avoid conviction and the disgrace of being forcibly removed from office.

Now, this is where things can get a bit technical, because the legal framework for the impeachment power is quite complicated. But, have no fear, the impeachment articles against Nixon can help us untangle the elusive meaning of impeachable offenses. The first article against Nixon directly referred to the Watergate scandal, as it mentioned the unlawful entry into the headquarters of the DNC. The article charged Nixon with partaking in an elaborate conspiracy to cover-up the criminal action. It went on to maintain that the president’s own reelection committee had conducted illegal acts to promote his election, which is a violation of democratic norms. The article also contended that when those acts became clear, the president not only withheld information, he also used his official power to prevent further investigative procedures. While both Democrats and Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee voted in favor of the article, only six of the seventeen Republicans did so. Therefore, the impeachment process against Nixon did not rupture partisan divides completely.[13]

The second article stated the strongest case for impeachment, as it charged Nixon with using the apparatus of the government in an unlawful way. According to the article, Nixon exploited resources and personnel from government agencies, such as the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the FBI, the Secret Service, and the CIA to create a secret investigative unit within the office of the president in order to gather information on political opponents through illegal and illicit means. The article contended that Nixon’s actions not only infringed upon individuals’ constitutional rights, but they also compromised the democratic process. As legal scholar Cass R. Sunstein concludes, this article gets to “the heart of what the impeachment provision is all about.” The vote in the Judiciary Committee on this article was the same as the first article with both Democrats and Republicans voting in favor, but still a majority of Republicans voting against.[14]

The last impeachment article dealt with Nixon’s refusal to hand over the infamous tapes. The article maintained that when Nixon refused the Judiciary Committee’s subpoena for the tapes, he was impeding a lawful investigation into whether or not he had abused his official power. The article suggested that Nixon’s refusal to cooperate threatened the principle of checks and balances on government authority and was thus an impeachable offense. By a very narrow margin, (21 to 17) the Committee voted in favor of the article. As to be expected, most Democrats voted favorably (19 to 2) while the majority of Republicans votes against (2 to 15).[15]

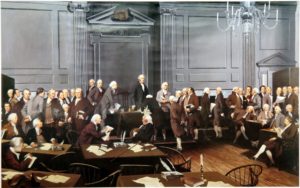

As the impeachment articles against Nixon suggest, impeachable offenses deal with grave misuses of official authority, purposeful disregard for the rule of law, systematic threats to civil rights and civil liberties, and orchestrated attacks on the democratic process. Impeachment, then, pertains to severe transgressions that pose a direct and immediate threat to American society. As Lichtman explains, “The framers adopted impeachment as a necessary check against tyranny.”[16] Article II, Section 4 of the United States Constitution addresses the impeachment process, stating, “The President, Vice President and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”[17]

With impeachment, early American political leaders confronted two concerns. On one hand, they wanted to ensure that there were checks on the president’s authority and, on the other hand, they wanted to make sure that the president would not be beholden to Congress.[18] To meet these concerns, they developed the “high crimes and misdemeanors” threshold for determining impeachable offenses as well as institutional protections (i.e. the two-thirds majority vote requirement in the Senate) to make sure that impeachment would only be used if there was a national consensus for such action.[19]

Because of these safeguards, impeachment has been rarely used. Due to its rarity, the legal limits to impeachment are not definitive. Simple misconduct or bad policy decisions by presidents are not necessarily high crimes and misdemeanors. Let’s say, for example, a president cheated on his or her taxes before being elected. Believe it or not, according to Sunstein, tax evasion is not an impeachable offense. As Sunstein explains, “It’s not an abuse of official authority. It’s in a wholly different category from the high crimes and misdemeanors that concerned Madison and Hamilton.”[20] To be sure, the president can be prosecuted after he or she leaves office. But while in office, Sunstein argues that the reach of presidential immunity most likely protects the president from criminal prosecution. So, while tax evasion is unbecoming of a president, it does not automatically entail an egregious abuse of official authority, which is the high crimes and misdemeanor legal standard for impeachment.[21]

Bad policy decisions are also not essentially impeachable offenses. Imagine, for instance, that a president issues an executive order increasing immigration regulations. In this scenario, many people believe the order to be unlawful and the Supreme Court eventually strikes down the directive. The president’s action in issuing the order is not an impeachable offense, so long as it can be established that he or she acted in good faith. Presidents are perfectly entitled to issue orders that they believe to be within their legal authority. In this case, the check on whether a president was wrong about the legality of a policy decision rests with the Supreme Court, not the impeachment process. Even if a president makes a wrongheaded policy decision, he or she is not automatically engaging in an egregious abuse of presidential authority.[22]

One of the thorniest aspects of the impeachment power’s legal scaffolding is determining if impeachable offenses are limited to those that occur while the president is in office. A number of scholars, including Noah Feldman and Jacob Weisberg, maintain that the founders intended for impeachment to only pertain to abuses committed while in office. Feldman and Weisberg point to the word “high” that the founders used to modify the “crimes and misdemeanors” description of impeachable offenses. According to them, “high crimes” has historically and legally referred to actions committed by high government officials in the course of their duties. No matter how serious the wrongdoing, Feldman and Weisberg insist that a president cannot be impeached for bad behavior committed before he or she has assumed the presidency. [23] Others disagree. Lichtman, for instance, maintains that there is legal precedent for applying impeachment to prior offenses. He points to the case of a federal judge who was impeached for abuses before assuming the bench.[24] Needless to say, this legal limit to the impeachment power is subject to debate.

Wait, (you might be thinking) what about prior crimes committed in pursuit of the presidency? That’s a great question. With Nixon, we were lucky in the sense that the subverting of the 1972 election and cover-up afterwards occurred while he was in office. But, let’s say, a new president is elected after scheming with a foreign government that is unfriendly to the United States. In this scenario, the newly elected president had worked closely with leaders from the other nation during the course of his or her campaign to spread false information about his or her political opponent. Is this an impeachable offense?

Yes, according to Lichtman and Sunstein.[25] For starters, Sunstein maintains that since the president procured the office through illicit means, that offense meets the “high crimes and misdemeanors” standard because it is connected to the presidency, even if it was committed before taking office.[26] As well, Lichtman argues that colluding with a hostile foreign nation to be elected is impeachable because such an action would “profoundly impact [the president’s] ability to govern, even subjecting him to foreign blackmail.”[27] Overall, these scholars conclude that if someone obtains the office of the presidency by conspiring with an unfriendly foreign government and other illicit means, then the democratic process has been compromised, the principle of self-governance has been undermined, and impeachment is necessary.

Obviously, the above scenario calls to mind the Russia investigation that is entangling our current president. So far, Robert Mueller’s special-counsel investigation into any scheming between Russia and the Trump campaign to warp the electoral process has produced indictments against two of Trump’s former associates, Paul Manafort and Richard Gates.[28] It remains to be seen the extent of the collusion with Russia and the extent of President Trump’s involvement. But, there are striking parallels between the Watergate scandal and the Russia investigation. The core of the impeachment case against Nixon was the carrying out of illegal and illicit acts to undermine the electoral process and covering it up afterwards. As historian David Greenberg puts it, “You start with the facts of wrongdoing: There were illegal crimes committed…in order to subvert the election. In both cases, there were suspicions it implicated the president.”[29]

Now, some might argue that collusion during the campaign is not an impeachable offense committed by Trump, because his actions as a candidate cannot count as an abuse of an office that he had yet to hold. I don’t agree with this assessment, but it is a plausible argument. Even so, there is a strong basis for impeachment, if it emerges that after assuming office Trump orchestrated a cover up of the Russia affair and impeded investigative procedures into the matter. Such actions would constitute a grave attack on our democratic principles and institutions, as he would be essentially trying to conceal a serious distortion of the electoral process.[30]

I’m going to end with a cautionary note. I abhor Trump. I did not vote for him and I detest his policies. Still, it is vital that all of us (Trump supporters and opponents) not rush to judgment. We need to let the special-counsel investigation gather all the necessary information. Only in this manner will our political leaders be able to make conscientious evaluations about what offenses, if any, have been committed. Impeachment is a powerful resource for checking presidential authority. But, we cannot let it be a simple political tool. The founders did not intend impeachment to be a weapon for one political group to use against another. If we are reckless and distort the process, we will disrupt the delicate balance of power that rests among our branches of government. While I believe Trump committed impeachable offenses, I know with certainty that we all have to be patient and allow for a thorough application of the law to the facts.

[1] Cass R. Sunstein, Impeachment: A Citizen’s Guide (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), 86-88.

[2] “Watergate Scandal,” History, 2009, http://www.history.com/topics/watergate (accessed 26 November 2017).

[3] Sunstein, Impeachment, 86-88.

[4] “Watergate Scandal,” History.

[5] Allan Lichtman, The Case for Impeachment (New York: Harper Collin, 2017), 28

[6] See, for example, Lichtman’s discussion of the illegal bombing that devastated Cambodia. Lichtman, Case for Impeachment, 35-36.

[7] “Watergate Chronology,” Watergate Info, http://watergate.info/chronology (accessed 26 November 2017).

[8] Lichtman, The Case for Impeachment, 28-31

[9] Ibid., 29.

[10] Sunstein, Impeachment, 90-91

[11] Lichtman, The Case for Impeachment, 30-32.

[12] Ibid., 1-3.

[13] Sunstein, Impeachment, 94-97.

[14] Ibid., 97-99.

[15] Ibid., 90-94.

[16] Lichtman, The Case for Impeachment, 3-4.

[17] “The Constitution of the United States: A Transcription,” National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript (accessed 26 November 2017).

[18] Sunstein, Impeachment, 152-153.

[19] Some argue that this safeguard protected Presidents Johnson and Clinton from being removed for flawed and problematic impeachment proceedings. See Sunstein, Impeachment, 99-116, 152-153.

[20] Ibid., 89-90.

[21] Ibid., 126, 162-163.

[22] Ibid., 124.

[23] Noah Feldman and Jacob Weisberg, “What Are Impeachable Offenses?” The New York Review of Books. 28 September 2017, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/09/28/donald-trump-impeachable-offenses/ (accessed 26 November 2017).

[24] Allan Lichtman, “More Rules to Impeachment,” The New York Review of Books, 26 October 2017, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/10/26/more-rules-of-impeachment/ (accessed 26 November 2017).

[25] Others argue that offenses committed in pursuit of the presidency are not necessarily high crimes and misdemeanors. See Feldman and Weisberg, “What Are Impeachable Offenses?”

[26] Sunstein, Impeachment, 122-123.

[27] Lichtman, “More Rules to Impeachment.”

[28] Joshua Nevett, “Donald Trump Impeachment Within Months’ claims expert who predicted his shock victory,” Daily Star, 1 November 2017 https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/politics/656473/donald-trump-impeachment-odds-president-allan-lichtman-russia-investigation (accessed 26 November 2017).

[29] Tim Marcin, “Trump’s America: What Watergate and Nixon’s Downfall Can Teach Us 45 years Later,” Newsweek, 17 June 2017, http://www.newsweek.com/trump-america-what-watergate-nixons-downfall-teach-45-years-later-626382 (accessed 26 November 2017).

[30] Noah Feldman and Jacob Weisberg, “More Rules to Impeachment, reply,” The New York Review of Books, 26 October 2017, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/10/26/more-rules-of-impeachment/ (accessed 26 November 2017).