How did we get here? I can barely even type the words that will encapsulate our collective future: President Donald Trump. Even now, I have a visceral reaction to typing out those words. But, that is enough about my emotions. This piece is not about my personal distress over the election of Donald Trump. I know a number of good people who voted for Trump. I do not want to alienate them; I do not want to argue with them. Rather, I want to understand their position. Moreover, as a historian, I want to unpack how we got to this place so that we can learn from the historical factors at play.

How did we get here? I can barely even type the words that will encapsulate our collective future: President Donald Trump. Even now, I have a visceral reaction to typing out those words. But, that is enough about my emotions. This piece is not about my personal distress over the election of Donald Trump. I know a number of good people who voted for Trump. I do not want to alienate them; I do not want to argue with them. Rather, I want to understand their position. Moreover, as a historian, I want to unpack how we got to this place so that we can learn from the historical factors at play.

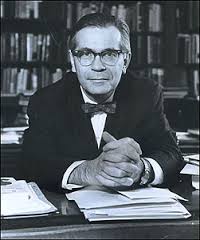

Donald Trump spent half as much money and had far less official infrastructure for voter turnout than Hillary Clinton, but he still won the election.[1] Trump won fifty-one percent of voters without a high school diploma. He gained the rural vote by sixty-two percent and the suburban vote by fifty percent. Fifty-three percent of men backed Trump and fifty-eight percent of white voters went for Trump.[2] One of the few people to predict a Trump win was historian Allan Lichtman. Lichtman, who was also my PhD advisor, explains Trump’s victory as being a result of the larger forces that shape American politics. According to Lichtman, presidential elections are primarily a referendum on the performance of the party in power. Despite President Obama’s strong approval ratings, the American people wanted a change from the Democratic Party’s leadership.[3]

Donald Trump spent half as much money and had far less official infrastructure for voter turnout than Hillary Clinton, but he still won the election.[1] Trump won fifty-one percent of voters without a high school diploma. He gained the rural vote by sixty-two percent and the suburban vote by fifty percent. Fifty-three percent of men backed Trump and fifty-eight percent of white voters went for Trump.[2] One of the few people to predict a Trump win was historian Allan Lichtman. Lichtman, who was also my PhD advisor, explains Trump’s victory as being a result of the larger forces that shape American politics. According to Lichtman, presidential elections are primarily a referendum on the performance of the party in power. Despite President Obama’s strong approval ratings, the American people wanted a change from the Democratic Party’s leadership.[3]

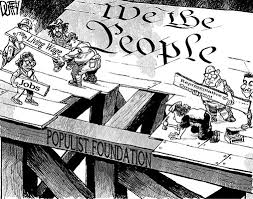

Others have called Trump’s win a populist insurgency. For instance, in an article published the day after the election, the New York Times describes Trump’s victory as the “rise of white populism.” As well, for a recent article in Salon, Jonathan Matthew Smucker asserts that Trump’s triumph marks the ascendancy of right-wing populism [4] But is Trump really a “populist”? And, just what is populism anyways? As Smucker puts it, populism usually involves living in a time “when political authority is no longer seen as legitimate by most people.” For Smucker, and others, populism is a broad movement that calls for the common people to come together to revolt against the establishment and various elites.[5] While this definition might give us a general sense of the Trump phenomenon, it is still too expansive for helping us unwrap the various layers that underpin the populist impulse.

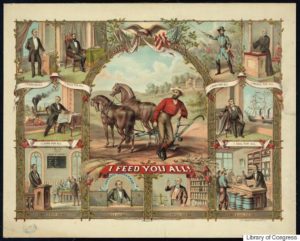

Indeed, pundits and journalists have thrown around the term “populist” so much these days that it seems like we have lost any meaningful understanding of the term’s implications. To understand populism in America, it might be helpful to retrace the historical origins of the term. The Populist movement started with the formation of smaller activist groups among southern and western farmers in the early 1870s. These groups included the Grangers, the Greenbacks, as well as the Northern, Southern, and Colored Farmers Alliances. The central goal of these groups was to resist the power of banks, big corporations, railroads, and other “monied interests.”[6] The movement culminated with the formation of the People’s Party in the early 1890s. The members of the party were known by the nickname Populists, or just Pops. In general, the People’s Party represented a coalition of grain and cotton farmers, coal miners, and railroad workers. The membership of the People’s Party proposed electoral reforms to push corruption out of the system and to make the government more transparent. As well, it advocated for a graduated income tax to make the wealthy carry more of the tax burden. Populists also demanded public control and regulation of banking, railroads, and other industries. Additionally, members of the People’s Party supported government involvement in the economy to help create jobs, build infrastructure, and provide relief to debtors.[7]

Indeed, pundits and journalists have thrown around the term “populist” so much these days that it seems like we have lost any meaningful understanding of the term’s implications. To understand populism in America, it might be helpful to retrace the historical origins of the term. The Populist movement started with the formation of smaller activist groups among southern and western farmers in the early 1870s. These groups included the Grangers, the Greenbacks, as well as the Northern, Southern, and Colored Farmers Alliances. The central goal of these groups was to resist the power of banks, big corporations, railroads, and other “monied interests.”[6] The movement culminated with the formation of the People’s Party in the early 1890s. The members of the party were known by the nickname Populists, or just Pops. In general, the People’s Party represented a coalition of grain and cotton farmers, coal miners, and railroad workers. The membership of the People’s Party proposed electoral reforms to push corruption out of the system and to make the government more transparent. As well, it advocated for a graduated income tax to make the wealthy carry more of the tax burden. Populists also demanded public control and regulation of banking, railroads, and other industries. Additionally, members of the People’s Party supported government involvement in the economy to help create jobs, build infrastructure, and provide relief to debtors.[7]

While the basic facts of the Populist movement appear straightforward, historians have not always agreed on whether we should celebrate or condemn the movement. To be sure, the first scholarly works on American populism often sang the praises of the People’s Party. These works were written during the Great Depression, when historians could readily sympathize with the Populists’ discontent as a part of their own fight for reform. In 1931, for example, scholar John Hicks wrote with reverence about the movement in his work, The Populist Revolt. Hicks argued that legitimate economic grievances motivated the farmers of the Great Plains to launch a brief but laudable revolt against plutocracy to challenge the unfair system that contributed to their hardships. Hicks concluded that the Populist goals of economic and political reform were later realized by the next generation of reformers in what became known as the Progressive movement. Ultimately, for Hicks, American populism was an admirable chapter in a long history of the haves versus the have-nots.[8]

While the basic facts of the Populist movement appear straightforward, historians have not always agreed on whether we should celebrate or condemn the movement. To be sure, the first scholarly works on American populism often sang the praises of the People’s Party. These works were written during the Great Depression, when historians could readily sympathize with the Populists’ discontent as a part of their own fight for reform. In 1931, for example, scholar John Hicks wrote with reverence about the movement in his work, The Populist Revolt. Hicks argued that legitimate economic grievances motivated the farmers of the Great Plains to launch a brief but laudable revolt against plutocracy to challenge the unfair system that contributed to their hardships. Hicks concluded that the Populist goals of economic and political reform were later realized by the next generation of reformers in what became known as the Progressive movement. Ultimately, for Hicks, American populism was an admirable chapter in a long history of the haves versus the have-nots.[8]

As World War II and the Cold War transformed the historical profession, scholars began to take a new look at the Populist movement. Writing during the hysteria of McCarthyism and in the shadow of the Holocaust, scholars of this era often emphasized the reactionary or the backwards-looking aspects of American populism. Most famously, Richard Hofstadter in The Age of Reform (1955), called attention to what he described as a curious blend of racism, nativism, and provincialism that took form in the Populist movement of the late Nineteenth Century. Hence, Hofstadter underscored the unsavory side of the movement. As he showed, the Populists had a tendency toward suspicion and overblown rhetoric. Many Populists saw sinister plots against liberty and opportunity forming not only among Wall Street elites but also among foreigners.[9] The 1892 platform of the People’s Party, for example, described, how “a vast conspiracy against mankind has been organized on two continents and is rapidly taking possession of the world.”[10] Another example is the case of Populist Tom Watson of Georgia. After the Populist crusade to seize the reins of government ultimately failed, the disillusioned Watson infamously went on to condemn Jews, Catholics, and African Americans with the same heated language that he once reserved for “plutocrats.”[11]

As World War II and the Cold War transformed the historical profession, scholars began to take a new look at the Populist movement. Writing during the hysteria of McCarthyism and in the shadow of the Holocaust, scholars of this era often emphasized the reactionary or the backwards-looking aspects of American populism. Most famously, Richard Hofstadter in The Age of Reform (1955), called attention to what he described as a curious blend of racism, nativism, and provincialism that took form in the Populist movement of the late Nineteenth Century. Hence, Hofstadter underscored the unsavory side of the movement. As he showed, the Populists had a tendency toward suspicion and overblown rhetoric. Many Populists saw sinister plots against liberty and opportunity forming not only among Wall Street elites but also among foreigners.[9] The 1892 platform of the People’s Party, for example, described, how “a vast conspiracy against mankind has been organized on two continents and is rapidly taking possession of the world.”[10] Another example is the case of Populist Tom Watson of Georgia. After the Populist crusade to seize the reins of government ultimately failed, the disillusioned Watson infamously went on to condemn Jews, Catholics, and African Americans with the same heated language that he once reserved for “plutocrats.”[11]

Unlike Hicks, then, Hofstadter found much to dislike and fear in the Populist movement. He believed that the Populists were primarily motivated by an anxiety regarding the industrial forces and cities that were replacing their status in the American economy and the American imagination. In all, Hofstadter saw the Populists as delusional, nostalgic agrarians who were misguidedly caught up in their romanticized version of the past.[12]

In Hofstadter’s view, the status anxiety and paranoia that fueled the Populist movement also shaped the Progressive reforms of the early Twentieth Century and the right-wing demagogy of the 1950s and 1960s. On the Progressive movement, for instance, Hofstadter contended that it was not a serious attempt to tackle fundamental economic reforms. On the contrary, he argued, it was a moral crusade launched by middle-class Protestants in an effort to recapture their declining leadership position from a nouveau-rich plutocracy on one hand and an urban immigrant political machine on the other.[13] Hofstadter also argued that the rise of Barry Goldwater had its roots in the Populist movement of the 1890s. As Hofstadter explained it, Goldwater conservatives believed that America had been “largely taken away from them and their kind.” He further explained that they believed that the old American virtues of competitive capitalism and independence had been “eaten away by cosmopolitans and intellectuals.” From Hofstadter’s perspective, both the Populists and the conservatives of the 1950s and early 1960s embraced absurd myths about the past and unfounded grievances about the present.[14]

In Hofstadter’s view, the status anxiety and paranoia that fueled the Populist movement also shaped the Progressive reforms of the early Twentieth Century and the right-wing demagogy of the 1950s and 1960s. On the Progressive movement, for instance, Hofstadter contended that it was not a serious attempt to tackle fundamental economic reforms. On the contrary, he argued, it was a moral crusade launched by middle-class Protestants in an effort to recapture their declining leadership position from a nouveau-rich plutocracy on one hand and an urban immigrant political machine on the other.[13] Hofstadter also argued that the rise of Barry Goldwater had its roots in the Populist movement of the 1890s. As Hofstadter explained it, Goldwater conservatives believed that America had been “largely taken away from them and their kind.” He further explained that they believed that the old American virtues of competitive capitalism and independence had been “eaten away by cosmopolitans and intellectuals.” From Hofstadter’s perspective, both the Populists and the conservatives of the 1950s and early 1960s embraced absurd myths about the past and unfounded grievances about the present.[14]

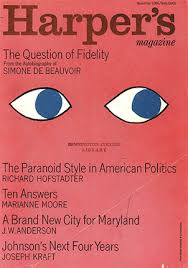

Thus, for Hofstadter, strands of paranoia and status anxiety are not exclusive to the right or the left wings of America’s political spectrum. In fact, Hofstadter argued in a later article, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” that a “suspicious discontent” has haunted all sides of the American political arena for centuries. In Hofstadter’s words, the typical adherent of America’s paranoid style of politics, “traffics in the birth and death of whole worlds, whole political orders, whole systems of human values.” For this type of person, as Hofstadter explained it, there “is always a conflict between absolute good and absolute evil, what is necessary is not compromise but the will to fight things out to a finish. Since the enemy is thought of as being totally evil and totally unappeasable, he must be totally eliminated.”[15]

Thus, for Hofstadter, strands of paranoia and status anxiety are not exclusive to the right or the left wings of America’s political spectrum. In fact, Hofstadter argued in a later article, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” that a “suspicious discontent” has haunted all sides of the American political arena for centuries. In Hofstadter’s words, the typical adherent of America’s paranoid style of politics, “traffics in the birth and death of whole worlds, whole political orders, whole systems of human values.” For this type of person, as Hofstadter explained it, there “is always a conflict between absolute good and absolute evil, what is necessary is not compromise but the will to fight things out to a finish. Since the enemy is thought of as being totally evil and totally unappeasable, he must be totally eliminated.”[15]

In many ways, then, it seems that Trump is following a long American political tradition—a tradition of exploiting rampant paranoia and anxiety about changing social and economic dynamics in order to garner support among the common people. During his campaign, for instance, Trump often talked about a “rigged system” and the need to “drain the swamp,” which mirrors the Populist movement’s discontent with the political class. Trump also combined his criticism of the political establishment with the dangerous scapegoating of marginalized groups. Over the course of his campaign, Trump described Mexican immigrants as criminals and rapists; he called for a ban on Muslim immigrants; he floated the idea of having a registry for Muslim Americans; he refused to condemn white supremacists who had campaigned for him; and he condoned the beating of a Black Lives Matter protester.[16]

Even though Trump’s campaign echoes the paranoia and anxiety that tainted the Populist movement, Trump, a celebrity businessman who happily flaunts his billions and sneers at “losers,” hardly seems to be a faithful follower of the ethos that shaped the People’s Party. As historian Michael Kazin reminds us, populism encapsulates more than just one historical moment in America’s history. As he describes it, populism is a “form of expression” that extols the virtue of the common people while distrusting elites as self-serving and undemocratic. According to Kazin, this populist impulse has been affecting American politics in varying degrees throughout the country’s history. In the truest sense of the word, then, Trump is not a populist, because his style and behavior fail to adhere to the populist emphasis on the noble assemblage of the “common man.”[17]

Even though Trump’s campaign echoes the paranoia and anxiety that tainted the Populist movement, Trump, a celebrity businessman who happily flaunts his billions and sneers at “losers,” hardly seems to be a faithful follower of the ethos that shaped the People’s Party. As historian Michael Kazin reminds us, populism encapsulates more than just one historical moment in America’s history. As he describes it, populism is a “form of expression” that extols the virtue of the common people while distrusting elites as self-serving and undemocratic. According to Kazin, this populist impulse has been affecting American politics in varying degrees throughout the country’s history. In the truest sense of the word, then, Trump is not a populist, because his style and behavior fail to adhere to the populist emphasis on the noble assemblage of the “common man.”[17]

With his bombastic attitude, however, Trump has been able to channel an important component of the populist drive: intense anger at the establishment. But, where is all this rage coming from? The sources of the current indignation have accumulated for a long time: the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; the collapsing public infrastructure; the growing economic inequality; the disappearance of manufacturing jobs; and the financial meltdown of 2008.[18] The Women’s Rights movement, the Civil Rights movement, and the push towards gay rights have chipped away at old societal hierarchies, but these movements have also caused anxiety for those who once benefitted from traditional societal divisions. Even more recently, immigration patterns have dramatically changed demographics in cities across the United States. These changes have put the nation on a trajectory in which white Americans will no longer occupy the majority position within a few decades. As a result, many white, (mostly male) working-class and middle-class Americans have come to fear that these changing socioeconomic and cultural factors may have robbed them of their birthright to prosperity.[19]

Hence, like the late-nineteenth-century Populists, the early-twentieth-century Progressives, and the conservatives of the post-World War II era, the ire of Trump supporters partially stems from their concern about the disappearing prominence of their social status. As Amanda Taub of the New York Times notes, the fear of social change is so powerful that it can often push voters to seek out an authoritarian or “strongman” leader. This type of leader will typically promise to restore order through enacting harsh, punitive policies against persons that have been deemed others or outsiders. As we have seen, President-elect Trump has made such assurances with his campaign declarations that he (and he alone) can “Make America Great Again.”[20] While Trump might not be a populist himself, he has been able to manipulate a significant thread of the populist sentiment as a means for gaining power.

Hence, like the late-nineteenth-century Populists, the early-twentieth-century Progressives, and the conservatives of the post-World War II era, the ire of Trump supporters partially stems from their concern about the disappearing prominence of their social status. As Amanda Taub of the New York Times notes, the fear of social change is so powerful that it can often push voters to seek out an authoritarian or “strongman” leader. This type of leader will typically promise to restore order through enacting harsh, punitive policies against persons that have been deemed others or outsiders. As we have seen, President-elect Trump has made such assurances with his campaign declarations that he (and he alone) can “Make America Great Again.”[20] While Trump might not be a populist himself, he has been able to manipulate a significant thread of the populist sentiment as a means for gaining power.

Even so, it would be grossly inadequate to explain away Trump’s election as simply being a result of white, working-class and middle-class Americans’ status anxiety and paranoia. Let me be clear: America’s long history with entrenched racism and sexism also contributed to Hillary Clinton’s defeat and Donald Trump’s win. But, it is vital that we recognize the economic resentment that also produced the desperation that gave way to Trump’s ascendancy.

So, what are these economic grievances? For starters, white working-class men’s wages plummeted in the 1970s and they took another hit during the economic disaster that was the Great Recession. For the most part, both parties have also supported free-trade deals due to the net positive GDP gains. But, these gains overlook the despair of the blue-collar workers who have lost work because jobs went abroad to other countries such as Mexico or Vietnam. The intangible consequences of these economic changes have also been dreadful for working-class men. As scholar Joan C. Williams explains it, manly dignity is a big deal for working-class men and, for them, that dignity still derives from being a breadwinner. In Williams’s words, “most men, like most women, seek to fulfill the ideals they’ve grown up with. For many blue-collar men, all they’re asking for is basic human dignity.”[21]

So, what are these economic grievances? For starters, white working-class men’s wages plummeted in the 1970s and they took another hit during the economic disaster that was the Great Recession. For the most part, both parties have also supported free-trade deals due to the net positive GDP gains. But, these gains overlook the despair of the blue-collar workers who have lost work because jobs went abroad to other countries such as Mexico or Vietnam. The intangible consequences of these economic changes have also been dreadful for working-class men. As scholar Joan C. Williams explains it, manly dignity is a big deal for working-class men and, for them, that dignity still derives from being a breadwinner. In Williams’s words, “most men, like most women, seek to fulfill the ideals they’ve grown up with. For many blue-collar men, all they’re asking for is basic human dignity.”[21]

There is an underlining point here that needs to be highlighted: the working class and the poor are not one and the same. Often times when liberals speak of the working class, they confuse that segment of the population with the actual poor, who are in the bottom thirty percent of American families. As Williams makes clear, though, the working class is actually comprised of those Americans who are literally in the middle. They are the fifty percent of families whose median income was $64,000 in 2008. “That is the true ‘middle class,” Williams explains, “and they call themselves either the middle class or working class.”[22]

While liberal policies have helped the poor for over a century, means-tested programs have excluded the working-class portion of the population. This omission helps to keep costs and tax rates down. But it has also caused resentment of the poor among members of the working class who do not understand why they have to pay for programs that do not benefit them directly. For example, around twenty-eight percent of poor families receive childcare subsides, but that assistance is missing for working-class families. By way of illustration, Williams’s article discusses the bitterness of her sister-in-law who works fulltime for Head Start. As Williams notes, her sister-in-law essentially provides free childcare for poor families even though she can barely afford childcare for her own children. In the end, the exclusion of the working class from the benefits of certain social policies has been a recipe for class conflict. Yet, the working class is not necessarily enraged at the top percent or the business elites. On the contrary, they are angry at the bottom percent of the population who has primarily benefitted from social programs and at the political establishment that created such policies. [23]

While liberal policies have helped the poor for over a century, means-tested programs have excluded the working-class portion of the population. This omission helps to keep costs and tax rates down. But it has also caused resentment of the poor among members of the working class who do not understand why they have to pay for programs that do not benefit them directly. For example, around twenty-eight percent of poor families receive childcare subsides, but that assistance is missing for working-class families. By way of illustration, Williams’s article discusses the bitterness of her sister-in-law who works fulltime for Head Start. As Williams notes, her sister-in-law essentially provides free childcare for poor families even though she can barely afford childcare for her own children. In the end, the exclusion of the working class from the benefits of certain social policies has been a recipe for class conflict. Yet, the working class is not necessarily enraged at the top percent or the business elites. On the contrary, they are angry at the bottom percent of the population who has primarily benefitted from social programs and at the political establishment that created such policies. [23]

Now, some liberals might argue that they are the ones that offer policies that could actually help the working class and that conservatives are only looking to further exploit blue-collar workers. And, I believe this sentiment to be true. I believe that the left holds the key to helping the working class. But, for the most part, members of the working class are not interested in current liberal proposals, such as a fifteen-dollar an hour minimum wage or paid sick leave. As Williams puts it, “A few days’ paid leave ain’t gonna support a family. Neither is minimum wage. WWC [white-working-class] men aren’t interested in working at McDonald’s for $15 per hour instead of $9.50.” Rather, what they want is the assurance of a secure, full-time job with solid wages. Moreover, what they are looking for is stable employment that will provide a sound quality of life for those without a college education. Ultimately, what they care about is the American promise that they believe past generations of their family members once enjoyed: the prospect of finding a reliable job that will deliver a respected place in one’s community and a sense of human dignity. [24]

Trump has exploited the feelings of desperation and resentment among the working class and he has concentrated it in a terrifying direction. Hofstadter, then, was correct to warn us about the paranoid style of American politics and its potential dangers. Still, as recent historical scholarship shows, not all aspects of American political history have been plagued by status anxiety, intolerance, and xenophobia. Looking at the Populists of the Nineteenth Century, historian Charles Postel argues that despite the xenophobia that tainted some parts of the movement, a great majority of the movement’s leaders, activists, and supporters still “went to their graves committed to the ideals of social justice.” For example, former Populist Clarence Darrow settled into the farmer-labor division of the Democratic Party. Mary Elizabeth Lease, often called the “Queen of Kansas Populism,” also found a place in the progressive side of the Republican Party. As well, political activist Henry Demarest Lloyd went on to join the Socialist movement created by former labor Populist Eugene V. Debs.[25] Thus, like so many other schools of political thought, the ethos that motivated the original Populists contains many dimensions. And, more to the point, one of those dimensions is a latent enthusiasm for making a more just society.

Trump has exploited the feelings of desperation and resentment among the working class and he has concentrated it in a terrifying direction. Hofstadter, then, was correct to warn us about the paranoid style of American politics and its potential dangers. Still, as recent historical scholarship shows, not all aspects of American political history have been plagued by status anxiety, intolerance, and xenophobia. Looking at the Populists of the Nineteenth Century, historian Charles Postel argues that despite the xenophobia that tainted some parts of the movement, a great majority of the movement’s leaders, activists, and supporters still “went to their graves committed to the ideals of social justice.” For example, former Populist Clarence Darrow settled into the farmer-labor division of the Democratic Party. Mary Elizabeth Lease, often called the “Queen of Kansas Populism,” also found a place in the progressive side of the Republican Party. As well, political activist Henry Demarest Lloyd went on to join the Socialist movement created by former labor Populist Eugene V. Debs.[25] Thus, like so many other schools of political thought, the ethos that motivated the original Populists contains many dimensions. And, more to the point, one of those dimensions is a latent enthusiasm for making a more just society.

We need to channel the potential dedication to social justice embedded in the populist impulse to stymie the tide of hate that has swept the country in Trump’s wake. To start, let us all, those on the left and on the right, resist the allure of our country’s darker, more paranoid style of politics. To paraphrase Hofstadter, let’s stop envisioning our political counterparts as being totally evil, totally wrong and, in essence, requiring total elimination. Simply put, we need to stop demonizing each other.[26] Yes, economic resentment has fueled racial anxiety, which has also hemorrhaged into all-out racism in a frightening number of Trump supporters. But, to simply dismiss every person who voted for Trump as a bigot or an appeaser of bigotry is dangerous and it will not stop the march of hate.

Let me be clear: I am not arguing that those on the left should give Trump a chance. I think his rhetoric and proposals are horrifying. But, I do think we can give some of the people who voted for him a chance. To bridge the gaps that are dividing our country, we need to reach out to the people that were economically motivated to vote for Trump. We need to build a broader movement that places sustained job development for blue-collar workers and education for new economy jobs at the forefront of its agenda. We need to show how creating a more equitable society for everyone is the key to securing true economic and political reform. This moment is frightening, but it does hold great potential. If we can move the current discontent in a more positive and inclusive direction, then we will be able to create a movement that is truly capable of challenging the entrenched power of the business and political elites.

Let me be clear: I am not arguing that those on the left should give Trump a chance. I think his rhetoric and proposals are horrifying. But, I do think we can give some of the people who voted for him a chance. To bridge the gaps that are dividing our country, we need to reach out to the people that were economically motivated to vote for Trump. We need to build a broader movement that places sustained job development for blue-collar workers and education for new economy jobs at the forefront of its agenda. We need to show how creating a more equitable society for everyone is the key to securing true economic and political reform. This moment is frightening, but it does hold great potential. If we can move the current discontent in a more positive and inclusive direction, then we will be able to create a movement that is truly capable of challenging the entrenched power of the business and political elites.

[1] Jonathan Matthew Smucker, “Right-Wing vs. Progressive Populism: How to win in these populist Trump times,” Salon, 13 November 2016, http://www.salon.com/2016/11/13/right-wing-vs-progressive-populism-how-to-win-in-these-populist-trump-times_partner/ (accessed 5 December 2016).

[2] “Reality Check: Who Voted for Donald Trump?” BBC News, 9 November 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/election-us-2016-37922587 (accessed 5 December 2016).

[3] Peter W. Stevenson, “Prediction Professor’ Who called Trump’s big win also made another forecast: Trump will be impeached,” Washington Post, 11 November 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/11/11/prediction-professor-who-called-trumps-big-win-also-made-another-forecast-trump-will-be-impeached/?utm_term=.1cf7ae2259cc (accessed 5 December 2016).

[4] Amanda Taub, “Trump’s Victory and the Rise of White Populism,” New York Times, 9 November 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/10/world/americas/trump-white-populism-europe-united-states.html?_r=0 (accessed 5 December 2016); Smucker, “Right-Wing vs. Progressive Populism.”

[5] Smucker, “Right-Wing vs. Progressive Populism.”

[6] “Populism,” Digital History, http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3127 (accessed 6 December 2016).

[7] Charles Postel, “If Trump and Sanders are Both Populists, What Does Populist Mean?” The American Historian, February 2016, http://tah.oah.org/february-2016/if-trump-and-sanders-are-both-populists-what-does-populist-mean/ (accessed 6 December 2016).

[8] John D. Hicks, The Populist Revolt: A History of the Farmers’ Alliance and the People’s Party (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnosotea, 1931).

[9] Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform: From Bryan to FDR (New York, Vintage Books: 1955), 36-82.

[10] “The Omaha Platform: Launching the Populist Party,” History Matters, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5361/ (accessed 6 December 2016).

[11] “Populism,” Digital History.

[12] Hofstadter, The Age of Reform, 60-94.

[13] Hofstadter, The Age of Reform, 11-12.

[14] Richard Hofstadter, “Paranoid Style in American Politics,” Harpers Magazine, November 1964, 81.

[15] Hofstadter, “Paranoid Style,” 77, 82.

[16] “Here are 13 Examples of Donald Trump Being Racists,” Huffington Post, 29 February 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/donald-trump-racist-examples_us_56d47177e4b03260bf777e83 (accessed 6 December 2016).

[17] Isaac Chotiner, “Is Donald Trump a Populist?” Slate, 24 February 2016, http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/interrogation/2016/02/is_donald_trump_a_populist.html (accessed 6 December 2016).

[18] Smucker, “Right-Wing vs. Progressive Populism.”

[19] Taub, “Trump’s Victory and the Rise of White Populism.”

[20] Ibid.

[21] Joan C. Williams, “What So Many People Don’t Get About the U.S. Working Class,” Harvard Business Review, 10 November 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/11/what-so-many-people-dont-get-about-the-u-s-working-class (accessed 6 December 2016).

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Postel, “If Trump and Sanders are Both Populists.”

[26] Hofstadter, “Paranoid Style,” 82.