To borrow from Joyce Appleby, I consider myself a practitioner of “practical realism.” I appreciate post-modern theorists’ suspicion of supposed essential universal truths; however, I still strive to obtain a degree of professional objectivity in my reconstructions and interpretations of the past.

In general, I investigate the interplay between language and ideas, particularly in the realms of religion, politics, gender, and the law. My current research examines the dueling civic ideologies embedded in the conflict over the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in order to shed light on the gendered ideas that have influenced social initiatives, political positions, and legal philosophies. In total, my work seeks to explore how the construction of ideas through language helps to create communal identities and values.

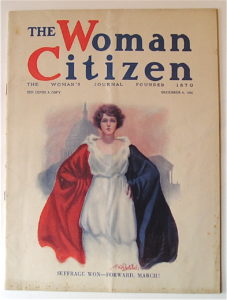

After studying early modern European history as an MA student, I turned my attention towards American history when I began my PhD program. I also started to use gender as my main investigative lens. The task of giving a lecture on the ERA for a course on women in America sparked my interest in the historic amendment. After the lecture, several students insisted that the ERA would not resolve the persistent disadvantages that restricted women’s societal position. To a significant degree, my research on the ERA can be understood as an attempt to provide an historical explanation for this contemporary dismissive attitude towards the amendment. My growing interest in the topic led to several projects, including, my study, “Resurrecting the Equal Rights Amendment,” which looks at why the amendment failed to secure enough state approvals. I also conducted an oral history project, “Voices of the ERA,” which uncovers the conflicting historical memories of ERA supporters involved in the state ratification struggle of the 1970s and early 1980s.

My latest research illuminates the ideological contours of the ERA conflict from 1920 to 1963. My book manuscript, Gendered Citizenship, which is based on my PhD dissertation, engages deeply with American legal and political history as well as the increasingly rich material on women’s and gender history. As a work that aims to capture the experiences and activism of the diverse group of individuals who participated in the original ERA conflict, my study is based on a wealth of primary source material, which includes a careful analysis of correspondence, public and private utterances, congressional testimonies, and several court cases. In the process, my study unearths the dueling civic ideologies embedded in the struggle: ideologies that I call emancipationism and protectionism.

As I describe it, emancipationism refers to a particular form of thought that developed after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and advocates for the absolute equality of men and women citizens before the law. It also comprises the core idea behind the pro-ERA position. As ERA supporter Donald Quigley Palmer of the American Newspaper Guild put it, “Adoption of the amendment is simple justice and the only means by which men and women will be given equal rights and equal responsibilities under the law.”[i] For ERA supporters, sex-based legal distinctions in the wake of federal woman suffrage created not only fluctuating definitions of women’s legal personhood, but also constitutional inconsistencies with regard to the rights of American citizens. Overall, ERA proponents supported the amendment as the best way to fully emancipate a class of electors to ensure that a single standard of rights applied to men and women citizens equally.

As I use it in my study, protectionism refers to a specific way of reasoning that primarily arose after the advent of federal woman suffrage that espouses the virtues of sex-specific rights. It also encompasses the core idea behind the anti-ERA stance, since ERA opponents criticized the amendment as a threat to the sex-based legal distinctions that upheld what they understood to be women’s natural right to special protection. As one anti-ERA pamphlet alleged, “Men and women are different in biological structure and social function. State laws regulating working conditions for women, family support, guardianship of children, property, and inheritance, marriage and divorce recognize these differences.”[ii] These two systems of thought ultimately clashed over the relationship between gender and citizenship, as emancipationists insisted that American ideals affirmed the right of men and women to participate as citizens on the same terms and protectionists maintained that true sexual equity demanded that the law be free to treat citizens differently on account of sex.

As a whole, my book manuscript, Gendered Citizenship, forcefully argues that the original ERA conflict is the essential narrative for understanding the changing character of American citizenship in the post-suffrage era. Thus, my work takes the struggle over the ERA in an entirely new direction. Rather than focusing on the familiar theme of why the ERA failed to gain enactment, my work explores how debates over the ERA redefined the concept of American citizenship from a single-gender (masculine) model to a dual-gender model. In all, Gendered Citizenship thoroughly examines the competing views of citizenship embedded in the long-running struggle between protectionists and emancipationists that transcended traditional liberal versus conservative disputes in twentieth century America. Moreover, my work demonstrates how the arguments and the activism of the protectionists forged a concept of dual citizenship that reflected a belief in inherent differences across the sexes and the need for special protection for women. Most importantly, as my work concludes, the protectionist belief in the equity of sex-specific rights still guides the dominant cultural consensus to the present day. Despite the generally, well-meaning approach of many protectionists, their victory in the original ERA conflict led to the advancement of a gendered concept of citizenship that justifies a lack of equal treatment for women and the perpetuation of sex discrimination.

While I am still working on my book manuscript, I have considered additional projects to explore over the upcoming years. A logical extension of my recent work would be a study on the birth control movement and its effect on the conception of a citizen’s rights. As well, I would like to complete a study that examines the different conceptions of masculinity embedded in the political philosophies of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Henry Wallace, and Harry Truman. In the end, I continue to be intrigued by the relationship between language and ideas, and its impact on politics, gender, and the law.

~Rebecca DeWolf, PhD

[i] U.S. Congress, Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, Equal Rights for Men and Women, Hearings, before a Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate, 75th Cong. 3rd sess., 7-10 February 1938, Committee Print, 182.

[ii] National Consumers’ League, “Don’t Buy a Gold Brick,” pamphlet, 1944, folder 21, box 3, Hattie Smith papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.